|

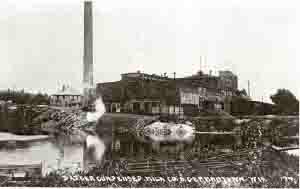

The original Gehl Creamery on Main Street was located near Western Avenue. The company was started in 1886 by Nicholas and his brother John Paul Gehl. The left picture is a view of the creamery looking northwest while the right picture is a view looking north. The left picture was taken about 1900 while the right about 1912.

Above, the second Gehl facility on east side of North Street at Main was called Badger Milk Products Company later to be named Gehl Guernsey Farms, Inc. On the left, a front view looking north. On right, a rear view looking southwest.

Gehl family records show in 1896 John Paul Gehl, son of Michael N. and Mary Anna (Fohl) Gehl of Nenno, was managing a small creamery owned by his brother Nicholas. The next year on 29 April he married Theresa Neubauer of Milwaukee. At the time Nicholas was in a brokerage business in Milwaukee and Theresa was his secretary. Owning John an amount of money, Nicholas deeded the creamery over to John in payment of that debt and as a wedding present. The creamery was located on the north side of Main Street just east of Western Avenue. From 1896 to 1909, John Paul made butter and cheese at the creamery. In 1909, the creamery was remodeled and a vacuum pan installed so the company could make sweetened condensed milk for the candy industry and plain condensed milk for ice cream manufacturers. In 1912 the facility was referred to as Gehl's Condensed Milk Factory but was officially named Badger Condensed Milk Company. The house next to the plant on its east is still standing [2003] and was John Paul and Theresa Gehl's home. The company also maintained two barns located behind the creamery for five teams of horses to pick up milk from farmers within a 15-mile radius of the creamery. The practice of picking up milk from the farmers started with his father Michael Gehl who had a creamery in Nenno, Wisconsin. Possibly as early as the 1880s he had one person with horse and wagon pick up separated cream from the farmers. But, the creamery maintaining a horse stable would seem to be a bit unusual for its time. Normally the farmers would have brought the raw cream/milk to the creamery. Having the creamery take over this responsibility it would seem was an innovation started by his father. As time went on and trucks were used, then moving the raw milk became an independent enterprise where someone with a refrigerated truck became a milk hauler, established a route, and was an intermediary between the farmer and the creamery in getting the raw milk to the milk plant be this the processing facility or a collection point. Would expect that the pickup of milk using horses started very early in the morning, say 4:00 or so, go out 15 miles, turn around, pick up the milk and make it back to the creamery at a respectable time that day. In 1913, J.P. Gehl decided it was advantageous to get into the evaporated milk business so he purchased the lime kiln property from the Nass Brother's Western Lime and Cement Company where he built a dairy plant in 1915. This would be further east on Main Street adjacent to and east of North Street. The plant was designed by Professor Huntziger of Purdue University. In 1919, possibly in 1911, the Gehl company acquired the Riverside Creamery in Allenton from William Hamm and turned it into a milk receiving facility the milk then transported to their plant in Germantown.

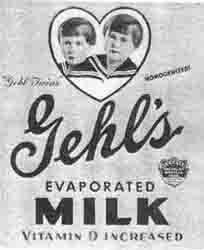

In 1920, John Paul incorporated the company and called it Badger Milk Products Company. Both men and women basketball team were sponsored, the men carrying the name Purity Milk and the ladies Badger Milk Maids. Pictures of these teams can be found here and here. At this time the company promoted the Gehl's Evaporated Milk brand. At the top of the label centered was a heart on which could be seen the portraits of Paul and Irene, twins of John and Theresa. In the 1927 Gehl's installed a fluid milk bottling operation and began selling to the Milwaukee market. Ford Titan trucks (20) for home and retail delivery were stored in Gehl's Germantown garage. In 1932 Milwaukee passed an ordinance requiring all milk sold in Milwaukee must be bottled in Milwaukee. So a Milwaukee plant was built that year at 35th and Capital Drive. The bottling operation was moved out of the Germantown Plant to the Milwaukee Plant. A July 1933 article in The Milk Dealer says "...Between 25,000 and 30,000 people visited the new plant. The garage at the rear of the plant was cleared out and converted into an entertainment room." White refrigerated Divco trucks delivered wholesale milk, ice cream, and frozen foods to stores in the Milwaukee area. A picture of these trucks can be found on page 55 in the book In 1935 the company changed it name to Gehl Guernsey Farms, Inc. From the early 1930's to the mid 1960's Gehl's operations remained essentially unchanged. The Germantown plant produced evaporated milk, butter, skim powder, sweetened condensed milk, and dehidra (i.e. milk crumb). The Milwaukee plant bottled milk and made ice cream. In 1967, the Milwaukee plant was sold to Hawthorne Mellody as Gehl's could no longer be competitive in the fluid milk business. In 1970, the Germantown plant discontinued the production of evaporated milk and butter and in 1976 discontinued skim powder operation. Dehidra was continued to 1988. In 1972 the company installed a Dole canning line to manufacture puddings in 5 oz. aluminum cans at 420 cans per minute. Gehl's secured Hunt Wesson as a customer and within several years was the sole supplier of Hunt's snack pack pudding for the entire country. Throughout the 1970's, 80's, and 90's Gehl's continued to expand its product line to include cheese sauce, iced coffee, diet and nutritional drinks. Today, as the company enters the 21st century and it second century of operation, the fourth generation of the Gehl family is about to take over leadership of the firm. Taking a walking tour through the Gehl facility in the mid 1950s, to the left of the main factory was located the warehouse where products were stored and filled evaporated milk cans boxed and put directly into railroad cars or on to wooden skids for truck delivery. Also stored there were bags of sugar used in the manufacturing process and bags of dehydrated milk. Working here were Bob Vehring, Warehouse Manager, and Vernon Marks. In earlier days the building was used as a garage and warehouse to park 20 trucks used to deliver milk products to Milwaukee. In the front east corner of the warehouse was the maintenance room. Ray Phillips was the maintenance person. Raw milk from the farmers in cans was brought to the facility in trucks. These trucks were unloaded outside on the east side of the plant facility on the equivalent of the second level. Just below this was a drive through tunnel where milk in bulk tanks could be brought in from the Allenton Facility, which was a receiving station, and tanks trucks could be loaded with milk and ice cream mix for delivery and processing at the Milwaukee plant. The main plant itself, taking a walking tour through it in 1958, you would have seen: Through the front glass main entrance door identifying the word "Gehl's" you would have entered the business office. It was a large room with a long tall wooden 18 or so inch wide counter which ran halfway across the room west-east. Behind the counter was the office staff. Elaine Marx and Lillian Schlaefer. To the left with an entrance from behind the counter was the plant manager's office. The plant manager was Oliver Peter Schulteis who worked at the dairy twenty-two years and as plant manager twelve years. Behind the plant manager's office was a small storage room. To the right on the east wall on its south side was the door leading into the plant proper. The room you entered contained two storage tanks going through the ceiling into the second floor used to hold raw milk that the truck drivers would bring in from the farmers. The sound in this room was a decibel or two higher, actually several decibels higher than the office area as the sound here was the sound of the plant. On the west wall north side was a stairs leading to the second floor. On the north wall east side was an opening to the plant's interior. As you went upstairs and turned left there were two large storage tanks used to hold cream to make butter. They were also used to make ice-cream mix that was then transported to the Milwaukee plant to make ice-cream. Pan men were Vincent White, Henry Gebhard upstairs, and Rueben Reichert downstairs. If you turned around and looked east from these storage tanks, this was where the raw milk was processed. In this area were six large storage tanks which were use to hold condensed milk until it was canned. Entering the plant interior the area to the left was the butter making area and also held the freezer. Ed Hansen was the butter maker. Continuing north you entered the great room. This room was two stories in height. On the right east wall on the second level were milk testing rooms. Hilmer Gebhard and Leon Olsen worked there. Below them on the first floor was a utility room with individual storage lockers. There was an open landing with tubular railing running the length of the second level which allowed access to the testing rooms. From the great room looking south, the stainless tanks on the second level could be seen as there was no north wall there. Back on the ground floor directly ahead was the great room at this point open and seasonally used to package ambrosia in wooden containers, say in the 25 pound range, for the Ambrosia Chocolate Factory in Milwaukee. It already tasted like candy. To the left in the great room was the equipment used to fill small metal cans with evaporated milk. The empty cans would come in on a conveyor line gravity fed and directed to a circular machine, referred to as the filler, the cans were sterilized, filled and sealed and the filled cans were directed out into the warehouse where they had a label attached and were packed into boxes then on to a conveyor belt being directed into railroad cars. Other times the filled boxes were stacked on to skids and stored in the warehouse for later truck shipment. The filled boxes were handled by Vernon Marks. The boxing machine was located just north of the maintenance room and along the warehouse east wall area. Clarence Groth worked the boxing machine. Dorothy Rosenthal, who owned one of those hard top retractable roof Ford cars, worked at the filler. The person who was responsible for the filler operation was Lawrence Bartell who lived in Menomonee Falls near Stoper Steel. On the west wall north side of the great room was a large door service area leading to the warehouse located maybe 20 feet west. Between these two building ran the railroad spur line and where the filled cars of empty evaporated milk cans and empty refrigerator cars were positioned. The tracks ran south to north. On the south side would be two cars containing empty evaporated milk cans and north of them were two to three empty refrigerator cars. The railroad cars of empty cans would have their center opening clear with the cans stacked side to side one on top the other on both sides of the car up maybe seven feet. There was a two step bench ladder running 1/2 the width of the car used to reach the top of the rows. The bench would be moved out of the way as you worked towards the bottom. You would take six maybe seven rows down at one time, one row at a time though, then go on to the next set of rows. Each person doing this job had their own technique. Position in the center of the card was a tray shaker, very noisy, which directed the cans into a gravity fed conveyor line to a belt driven uplifting line maybe 16 feet. It is at this point the cans headed down to the filler machine. A fork of about four feet in width was used to take fork full by fork full of cans and place them on to the shaker to be directed inside to the filler. A fork full would be four layers of cans in the form of a pyramid as the left and right cans, which would have fallen, were stacked on top. John Baertlein was the expert here. When the railroad card was empty, one person would climb up one side where the brake wheel was position and release it. Another person would use a leaver and position it next to the car's back wheel pushing down on the handle causing the railroad car to move. Once it began to move it could be easily pushed across the road. What could not be perceived when driving over the spur on Main Street is that the grade was slightly down hill. Once you had the car rolling it gained speed. As the car cleared the road the person would reset the brake and stop the car. Both people then would do the same to the full can car and get it into position to connect the shaker to the can line. Once done the cans started rolling again. You are now back in the great room and on the north wall, on its west side was an opening into the "powder room." The majority of this room was filled by an oven. Milk in a very fine pattern was spayed into the oven and as it descended it dried and upon hitting the bottom was turned into powder. This powder was directed into pipes where in the northeast corner of the room it was place into 100 pound bags. Also in this room the product dehidra was made and placed into bags of 100 pounds each. The mixture went through a vacuum and then came out at the bottom where a 10 foot long hammer mill was located which pulverized dehidra and it was then blown up and came down a shoot just to the east of the dry power shoot. The sugar used for it came in railroad cars in 100 pound bags which had to be unloaded and put on to skids. What a back breaking job. On the other hand, Earl Marks could throw those 100 pound bags around like they were pillows. It was this sugar combined with milk that became dehidra. Bill Gildemeister on days and Clarence (fox farm) Wolf of Goldendale on second shift ran this operation. On the north wall on its west side was a tunnel maybe 20 feet long leading out to the back of the facility. The tunnel and all the entrance ways coming from the back to the great room were wide so a loaded skid could be easily moved through either for pickup or delivery. Once outside to your right (east) was the furnace, a very large room with the furnace in the center and pipes all over as this is were hot water and steam were produced. Positioned next to the furnace room was the smoke stack. Romy Zander worked the furnace. What was a bit unusual were the water spigots. You always found two turn off/on knobs. One controlled cold water. Out of the other controlled steam which came out under a reasonable amount of pressure. Should you have lost your grip on the hose, the hose would come alive and acted like a snake gushing out steam and flipping itself all over the floor. The trick now was not to attempt to grab the nozzle for a wrong move here and you were scalded, but to walk on the hose until you came to the nozzle and then carefully you could grasp it. This lesson you needed to learn but one time. Down the west side of the warehouse ran a service road, previously known as North Street but at this time used only by the dairy running from Main Street to Fond du Lac Road. Milk trucks hauling milk from the farmers would come in off of Fond du Lac. Coal trucks would come in off of Main Street. The back of the dairy for forty to sixty feet was a service area which lead east around the building to the milk inputting area where we started this tour. All these roads were top dressed with coal cinders with the exception of the milk receiving area which was blacktoped. Those identified working in the plant are not necessarily all who worked there but those that can be remembered. Back in the early 1950s Ann (Siegl) Schulteis, who lived a few blocks north of the dairy, remarked she needed to consider the wind direction before hanging her cloths on the outside wash line. Back in those day there were no indoor cloths dryers as you used the sun and the wind to dry the clothes. Seems that if the wind was blowing in a northerly direction, and she had hung her clothes out that morning, by afternoon when she brought them in they would be dirtier than before they were washed. The smoke billowing out of the smoke stack carried along with it much soot which was deposited throughout the neighborhood. Wash day at her house required a north wind and a prayer that it did not change half way through the day. The time is the late 1940s. I was nine years old. It was summer and the sun was shining brightly. When the sun came up that morning nothing said this was going to be a special day. To the contrary, it was a day like any other day that summer. We needed to find something to keep ourselves busy. I am sure I planned to do that day the same as I did the day before. As the morning came and went nothing much changed from the day before. We ate lunch but then something happened. There was a commotion beginning to happen at the back of the dairy by the quarry. Being at that age when everything is interesting, I hopped on my bicycle and headed in that direction. Turned on to Gehl's back entrance off of Fond du Lac and immediately knew something was up as there were a few cars parked along the side. Now there are never ever any cars parked on that narrow coal cinder service road. The only people every using it were the milk trucks drivers bringing raw milk to the dairy from the farmers to the north. Slowly I inched my way forward and when I came to the back of the dairy you could see grownups and mostly children (15-20) standing there looking into the quarry area. What was unusual were two of the house delivery milk trucks, backed up to the quarry and someone from their back was throwing out boxes. These must not have been the only trucks making delivery that day for the quarry landing was plumb full of these boxes from the top down to the water. Got off my bicycle and watched just like everyone else. You knew there was jubilation in the air. The excitement seem deafening although no one was talking. You just knew that St. Nicholas had arrived and left some presents. We did not know it at the time but it seems that the Milwaukee plant had made a batch of popsicles and something went wrong. Whatever went into this particular batch did not blend very well and rather than have the popsicle be a solid color, be this red or orange or grape, for this batch you saw white specks half the size of a pea throughout. There was absolutely nothing wrong with them other than they didn't look quite right and therefore could not be delivered to the stores for purchase. Milwaukees loss was Germantowns gain. As the trucks departed the kids descended each grabbing a box, made no different what the color was, and headed home. I was no different. It didn't make much difference if you took one box or five, although you could not carry five for what were you going to do with them when you got home. Put them in the freezer of the refrigerator, five boxes, heck you couldn't even get one in. So you put in as many as you could and what was left you went outside, sat down and with your brothers and sister and ate to your hearts content, and then they were gone. This was the day for by the next all had melted. On that one day I probably ate more popsicles than on all the other days that summer put together. You could throw in the previous year too. That day I remember as Popsicle Day in Germantown. |